The “State” of Biometrics: Navigating the Murky Waters of Biometric Laws in the U.S.

Effective fraud prevention requires advanced technology that stays ahead of the fraudsters, something that biometrics has long-promised. But biometrics technology is fast-evolving, which makes it hard for lawmakers to keep up. Across the U.S., different states have different definitions and legislations for biometrics. Meanwhile, there is a growing demand for nationwide data privacy regulations, similar to GDPR or California’s CCPA. In 2019, 51 prominent tech CEOs urged Congress to establish a federal data privacy law that would take precedence over state-level regulations—and this idea has only gained more traction as the need to streamline compliance efforts and bolster individual data privacy rights becomes ever more apparent. All these pressures are creating murky waters for Financial Institutions (FIs) to navigate. And the stakes are high: potential legal liabilities, heightened compliance costs, and growing public apprehension over privacy concerns leave little margin for error.

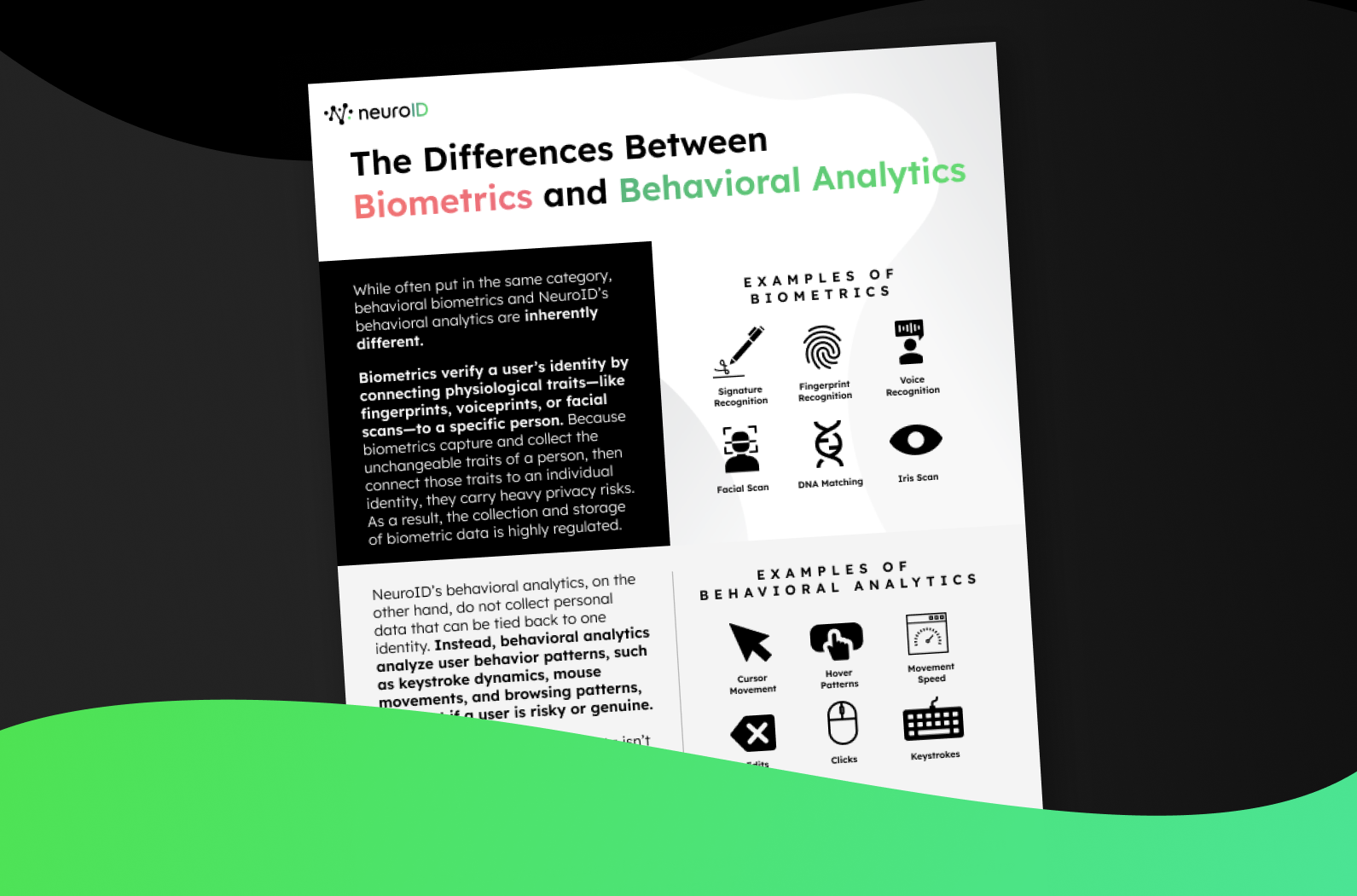

NeuroID, being a fraud detection and prevention solution provider, is closely monitoring the rising waves of legislation—even though we provide a behavioral analytics, not biometrics, solution. The two technologies are commonly confused, primarily because they’re both used for assessing fraud in ways that connect directly to real-time human activity (instead of historical credit scores, for example). But biometrics and behavioral analytics have distinct differences. The legally defining feature of biometrics is its ability to link data to one unique individual by capturing immutable traits of a person then connecting those traits with a specific identity. Behavioral analytics, although it may assess similar metrics as biometrics, does not gather data for the purpose of linking that data to one identity. Instead, behavioral analytics interprets digital interactions to anticipate risk. Actions like clicking, editing, or hesitating on a website produce behavioral data, which behavioral analytics evaluates to draw insights. While both technologies evolved to ensure secure digital interactions, they address this need differently: biometrics identifies unique individuals, while behavioral analytics identifies patterns to deduce intent.

This distinction is important for many reasons, but in this post, we’ll look at how it determines legal compliance within the U.S. and where that might lead us in the future.

Current U.S. Biometric Laws

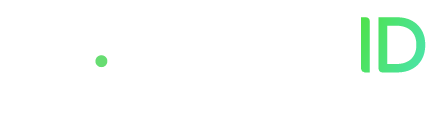

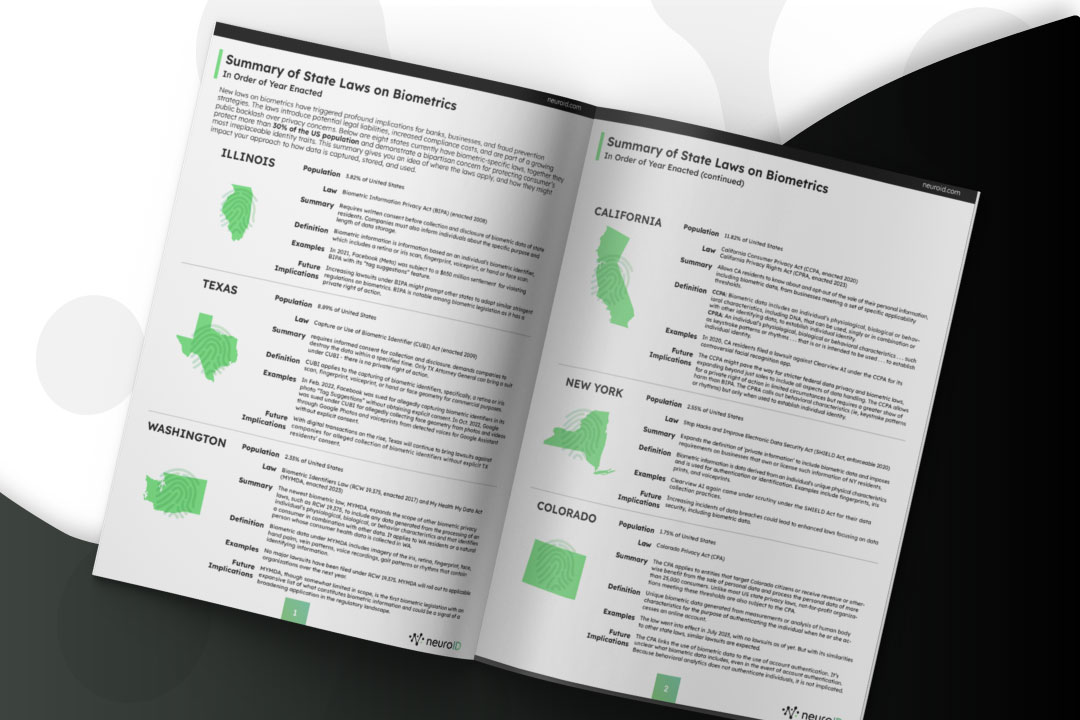

Although deployed in just a handful of states, biometrics legislation is already influencing how over 30% of the American population’s data are handled. It’s an easy talking point for bipartisan policies, bound to grow as more states are pressured into adopting similar regulations and consider the social, cultural, and legal ramifications. For anyone vested in the power of anti-fraud technology, understanding these laws and the data they apply to is paramount.

Illinois

Home to 3.8% of Americans, Illinois passed the Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) in 2008. Under BIPA, entities must obtain written consent before collecting and disclosing residents’ biometric data, defined as a retina or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or hand or face scan. This law, however, is not without its pitfalls. Case in point: in 2021, Facebook (now Meta) had to fork over $650 million in a settlement for allegedly violating BIPA. The stringent measures of BIPA, particularly its private right of action, suggest that as lawsuits surge (thus proving the law’s need) other states might follow suit in creating similar regulations. In fact, many point to BIPA as the original turning point for Texas, California, and other states that did implement later laws.

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

Texas

In the Lone Star state, home to 8.9% of Americans, the Capture or Use of Biometric Identifier (CUBI) Act has been in effect since 2009. Like BIPA, CUBI necessitates informed consent for data collection. Similar to BIPA, this law applies to biometric identifiers such as iris or retina scans, fingerprints, voiceprints, and hand or face geometry. CUBI departs from BIPA in that only the Texas Attorney General can file lawsuits, a departure from BIPA’s private right of action approach (in the private right of action approach, plaintiffs can receive steep statutory damages of either $1,000 or $5,000 per claim, leading to substantial awards where large classes of plaintiffs have been certified). Texas’s approach is more company targeted and has been applied as such. In 2022, both Facebook and Google faced ramifications for their biometrics use under CUBI.

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

Washington

While encompassing only 2.3% of Americans, Washington’s most recent biometric law could set the tone for broader legislation. The state’s My Health My Data Act (MYMDA), enacted in 2023, broadened the definition of biometric information to include data generated from processing an individual’s physiological, biological or behavioral characteristics. This expansion, even if explicitly limited to health data in scope, might hint at wider-reaching regulations in the future.

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

California

California, with 11.8% of Americans, has been a trendsetter in biometrics legislation. The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), enacted in 2017, and the subsequent California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) introduced in 2023, give residents a say over their data. CCPA is considered the most comprehensive consumer-oriented privacy law in the U.S., with its focus on additional privacy protections, including for “sensitive personal information” and the right to opt out of “sharing” data, not just “selling” data. The law also includes privacy obligations for California employers, making it unique among state laws.

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

New York

In the Empire State, home to 2.6% of Americans, the Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security Act (SHIELD) was passed in 2019. The SHIELD Act addresses the security of private information, broadens the definition of a data breach, and imposes more stringent data security requirements on companies. It expands the definition of “private information” to encompass biometric data, email addresses with their corresponding passwords/security questions, and financial account numbers. The SHIELD Act requires businesses to notify affected New York residents of a data breach and mandates notification to the New York Attorney General, the Department of State, and consumer reporting agencies in cases of large-scale data breaches.

Significantly, the SHIELD Act applies to any business that collects or uses biometric data of New York residents, even if that business is not New York-based—further underscoring the importance of biometric programs that keep pace with the fast-evolving legal landscape.

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

Colorado

Applying to just the 1.8% of Americans living in Colorado, the Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) is unique in that it targets not only for-profit entities but also non-profits. Many non-profits won’t be impacted, as the specific criteria for required compliance is atypical to the non-profit space: “control[ing] or process[ing] the personal data of at least 100,000 Colorado consumers during a calendar year; or deriving revenue or receiving a discount on the price of goods or services from the sale of personal data and processor control the personal data of 25,000 consumers or more.” Still, this remains an unusual and nuanced reach into the non-profit space, where many do not have the privacy infrastructure that for-profit businesses do.

The CPA also doesn’t single out biometric data for special treatment in the way other biometrics laws do, such as the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA). However, given that biometric data would generally be considered personal data, the processing of biometric data would theoretically be subject to the CPA’s broad requirements, including consumer rights to access, correct, and delete such data, and to opt out of certain processing activities. Without that legislative definition, controllers look to the definition of “biometric data” in Colorado’s data breach notification statute, which defines it as “unique biometric data generated from measurements or analysis of human body characteristics for the purpose of authenticating the individual when he or she accesses an online account.”

That definition is likely too restrictive in practice because it links the use of biometric data to account authentication. However, no biometrics lawsuits have been filed under CPA to date, leaving a murkiness around how it would generally be defined.

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

Connecticut & Virginia

While these states hold only 1.08% and 2.53% of Americans, respectively, their laws on biometric data set the scene for what could become the standard, with a clear emphasis on consumer consent around any use of physical biometrics.

The Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA) prohibits companies from processing biometric data without first obtaining consumer consent. It requires companies to create a way for consumers to easily revoke their consent, which would require an immediate halt to the processing of their biometric data. CTDPA follows Texas’s CUBI framework in that it does not create a private right of action; instead, the power lies solely with the Texas attorney general to enforce violations.

Similarly, The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) gives consumers the right to access their personal data and request that businesses delete it. It also requires companies to conduct data protection assessments related to processing personal data for targeted advertising and sales purposes. The VCDPA even contains some restrictions on the use of de-identified data or data modified to no longer directly identify individuals from whom the data were derived. The VCDPA classifies biometric data as “sensitive data,” which has its own subset under personal data, and treats it with more rigorous restrictions: “The VCDPA prohibits the processing of sensitive data without obtaining consumer consent. The processing of sensitive data also triggers the obligation to conduct and document a data protection assessment.”

Does it apply to behavioral analytics? No.

Pending U.S. Biometrics Laws

The legislation above is just the first wave of biometric regulation. Especially as existing mandates are tested in courts of law, many more states are expected to follow suit with biometric protections. Here are short summaries of the additional regulations under discussion as of this article’s publication.

Arizona (2023 AZ S.B. 1238):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, requires private entities with biometric data to create a policy, retention schedule, and consent before collection, allowing recovery of damages.

Hawaii (2023 HI H.B. 1085):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, mandates private entities to develop policies, retention schedules, and obtain consent for biometric data, allowing damage recovery.

Illinois (Various Bills):

Bills amending BIPA, exempting healthcare employers, allowing collection for security purposes, excluding mathematical representations from “biometric identifier,” and altering consent and damages provisions.

Kentucky (2023 KY S.B. 239, 2023 KY H.B. 483):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, requires private entities to create policies, retention schedules, and obtain consent for biometric data, with damages and Attorney General enforcement.

Maine (2023 ME H.P. 1094):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, covers non-employee biometric data, requiring policies, consent, disclosure, and destruction, with damages and Attorney General enforcement.

Maryland (2023 MD S.B. 169, 2023 MD H.B. 33):

Covers non-employee biometric data, mandates policies, consent, disclosure, destruction, prohibits employee tracking, and discrimination, with damages and Attorney General enforcement.

Massachusetts (2023 MA S.B. 195):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, requires policies, consent, and damages, with Attorney General enforcement, plus consent for biometric data processing, reporting, and data security.

Minnesota (2023 MN S.F. 954, 2023 MN H.F. 2532):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, mandates policies, consent, and damages.

Missouri (2023 MO H.B. 1047, 2023 MO H.B. 1225):

Requires policies, consent, prohibits conditioning services on biometric data collection, and allows damages.

Montana (2023 MT S.B. 351):

Requires storing “genetic data of Montana residents or biometric data” within the U.S., subject to Attorney General enforcement.

Nevada (2023 NV S.B. 370):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, mandates policies, consent, and damages, with violations deemed deceptive trade practices.

New Jersey (2022 NJ S.B. 3499):

Prohibits facial recognition at retail or public places except for safety, with penalties.

Pennsylvania (2023 PA H.B. 926):

Similar to NYC Ordinance, requires clear notice and bans sale, trade, or sharing of customer biometric data, with private action.

Tennessee (2023 TN S.B. 339, 2023 TN H.B. 932):

Similar to Illinois BIPA, mandates policies, consent, and damages, with penalties under Consumer Protection Act.

The Future of Biometrics

As the biometrics landscape changes, so should the strategies of FIs that rely on biometric data to protect their customers. Expanding fraud and identity stacks to include modern, cutting-edge solutions like biometrics is vital to keeping up with attackers. But biometrics come with a high responsibility, and must be applied thoughtfully. These laws are beginning to shape the direction of what may be best applied where.

For a deep dive into best practices in biometrics and a thorough understanding of behavioral analytics, read our new report: Biometrics and Behavioral Analytics Explained: From Myths to Mandates. It’s a good first resource for staying ahead of the curve and ensuring your biometric strategies align with both innovation and legislation.